Faux Expressionism: Simulation, semiotics and movement in the digital age by Gian Sanghera-Warren

“I wanted to hypnotise myself with data, with coloured pixels, to become vacant, to overwhelm any creeping sense of who I actually was, to annihilate my feelings … And then again I wanted to declare my presence … I wanted to look and I wanted to be seen, and somehow it was easier to do both via the mediating screen.” – Olivia Laing, The Lonely City.

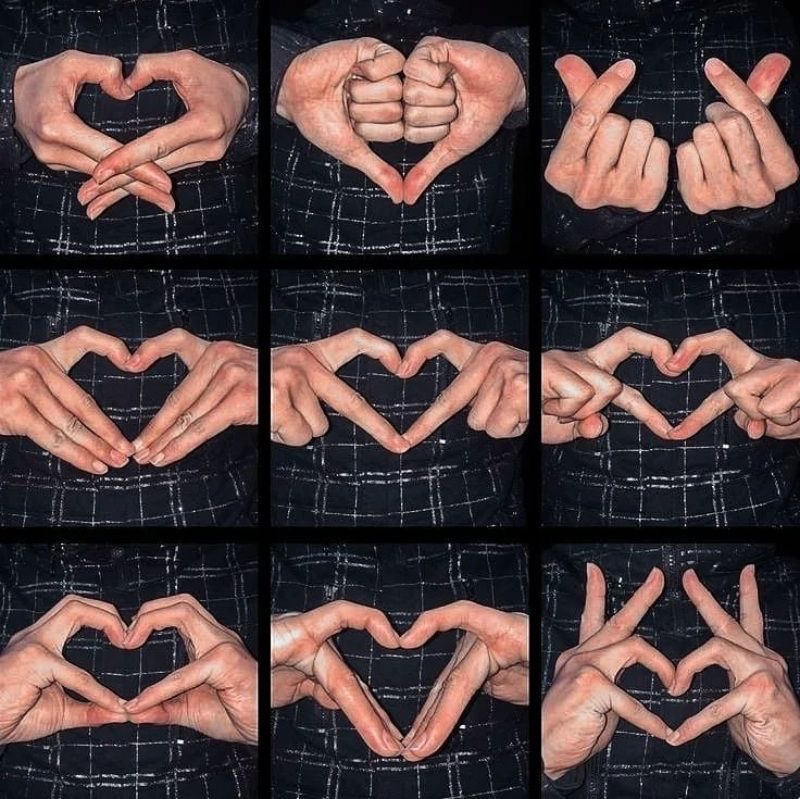

In a viral TikTok from 2022, influencer Julia Carolan suggests “If you want to know how old someone is, but you don’t want to ask them directly, ask them to make a heart with their hands.” Digesting this claim, Frenkel deconstructs the history of heart symbolism, from the symbol devised by a 14th-century physician to the 1990s “heartlike images constructed with letters and numbers” and the modern emoji. The physical gesture of a heart has transitioned in recent years, erasing the use of the thumb for a curved index and extended middle finger. This can be abstracted even further with a one-handed version, inspired by the simple approach of thumb and finger overlapping adopted across many East Asian countries. The distillation of love, from complex emotional and embodied feeling to one initiated from our physical heart is abstract to begin with. Thus, the transition from physical heart to metaphysical heart shape, then recreated as a hand gesture that has evolved across generations and cultures to be performed as a ritual of niche social coding speaks to Baudrillard’s notion of simulation and the eventual fourth stage of pure simulacra. The gesture we are left with feels far removed from the original source and yet resituates love within the body once again, reinventing the primal embodiment of deep emotion in a new abstract form both devoid and filled with meaning.

This research interrogates the role of expression within digitised movement through the framework of simulation, post-humanism and semiotics. Reframing doom-scrolling as a form of research, we can analyse and reframe online movement trends, presenting a new era of post-post-modern dance, referred to as Faux Expressionism. Drawing on Baudrillard’s 1981 theory of Simulacra and Simulation and semiotics, perhaps the expressionist trend of representing emotion through movement now exists in a hyper-real landscape where the symbols bear no relation to the meaning they once represented. Embracing the impact of virtuality on embodiment, inspired by the cyborg post-human era described by Haraway and Hayles, Faux Expressionism provides a methodology to embrace the synthesis of the physical and virtual body, whilst fundamentally destabilising the relationship between sign and referent. This work reveals the fallacy that expressive meaning exists behind movement and embraces the hyperreal landscape of pure simulacra that Faux Expressionism provides.

Defining Faux Expressionism

Faux Expressionism is the movement of a vastly digital age. Rejecting post-modernist pedestrian trends, expressionism is back, but this time it’s fake. In Baudrillardian fashion, the simulation of emotion has become so far removed from the true concept that it bears no relation to the feeling it once represented. Things still make us feel, but in ways we don’t understand. We’re left with a new reality, saturated with heart symbols thrown up like gang signs, TikTok dance trends and carousels of seemingly unrelated images set to a Lana del Rey song. And yet, even in this realm, a trace of the true self remains in the false self.

Since the invention and domestication of smartphones, surveillance cameras and motion-cap technology, movement has become increasingly recorded, flattened to the two-dimensional and available for redistribution. In the mid-2000s we Just Danced to Ke$ha in our living rooms, whilst Wii remotes matched our wrist swings to faceless avatars. Dancing became not only a virtual realm but a game, fuelled by the competition inherent to techno-capitalism.

The post-modernists of Judson Dance Theatre and friends aimed to strip movement of its emotion. But 60 years after Yvonne said No to moving and being moved, emotion is overwhelming. Split between the extreme highs and lows of the 20teens, Gen-Z and Alpha are prescribed Ritalin and Adderall to tame their 7-second attention spans whilst simultaneously binging on ketamine and blissing out to ASMR vids before bed. Pedestrian movement no longer relates to pedestrian life whilst complete abstraction seems impossible in a time of heightened feelings and infinite symbolism. Every gesture has been memified, every image is referential.

Enter Faux Expressionism, minimising Graham’s “hidden language” to a 4:3 ratio. Scrolling on TikTok, movement speaks to current moods more articulately than any sociologist. But even philosophers are made accessible, in videos that girlify the deep dissatisfaction with the modern world that the likes of Foucault and Camus expressed, simultaneously being presented on an app that is the virtual embodiment of the panopticon, the algorithm becoming our greatest prison. Simultaneously it’s our salvation. Touching grass works for some, but nothing makes us feel more seen than a compilation of capybaras being bonked. Movement of the digital age is beyond relatable, it’s transcendent, connecting to inner desires we never knew existed, unearthing esoteric responses that make us feel as if the digital landscape was carved out solely for us, despite the thousands of mutuals commenting “same”.

Rationale

This text contextualises an embodied physical research on the role of expression within digitised movement and documents the development of a theory, referred to as Faux Expressionism. By collating a vast amount of digitised movement that has entered a personal algorithm over the past year, the expressionist trend of representing emotion through motion seems to be resurfacing online. Rooting this research within a historical evolution of expression within movement, we can draw on and challenge a definition of expressionism that is closely related to the Latin exprimere, which translates as to squeeze out, suggesting that dance conveys “an outward, observable manifestation of inner feelings or thoughts”. Steele claims that the nature of modern dance evolved from the body being confronted by the machine, with choreographers responding to the increasing factories and urban living of the 20th century. Faux Expressionism continues within this lineage of the body being shaped by the machine, examining how movement from the digital age can be adopted to shift our concept of expression. Discussing television, Auslander quotes Marx’s Grundisse, reminding us, "In all forms of society, there is one specific kind of production which predominates over the rest''. While industrial production may have been the most dominant technological advancement precursing modern dance, our lives and bodies are now shaped by newer technologies. Therefore, digital production should be examined in relation to how it has redefined expressionism, particularly within the context of late-stage techno-capitalism.

Whilst we have observed a resurfacing of expressionism online through the prevalence of heart symbol gestures, fancams and viral dance trends, these representations are a form of what Baudrillard defines as simulation: they are purely symbolic images that have no connection to the meaning they relate to. The term Faux Expressionism reinforces that the notion of emotive movement expressing meaning is a fallacy. Instead of being critical of the influx of images devoid of meaning, the potential of this material to reveal something new about the expressive quality of movement within our lives is intriguing. In A Cyborg Manifesto, originally published in 1985 and made available online in 2016, Haraway suggests that whilst we have become “fabricated hybrids of machine and organism”, our machines are “disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert”. Before the invention of the internet, Haraway seemed to predict the increasing expression of our virtual selves and the subsequent eroding of our ‘IRL’ activity. Hayles supports this, arguing that “embodiment has been systematically erased in the cybernetic construction of the posthuman”. Thus, perhaps the increasing distillation of expressive movement to a series of hand gestures and viral dances could reshape how humans experience and convey emotion.

Semiotics

This research sits within the field of semiotics, whereby scholars aim to uncover the relationship between signs (words, gestures etc.) and the referents (objects, events, feelings etc.) they represent. According to Sebeok:

“Human intellectual and social life is based on the production, use, and exchange of signs and representations. When we gesture, talk, write, etc. we are engaged in sign-based representational behaviour, since representational activities vary from culture to culture, the signs people use constitute a mediating template in the worldview they come to have.”

Sebeok highlights the ability of signs to communicate meaning between individuals and their culturally specific nature, defining the “symbol” as a sign that stands for its referent in an arbitrary way such as “a V-sign made with the index and middle fingers can stand symbolically for the concept 'victory'”. Barthes refers to the connotations or “‘mythological’ effect” of an image, suggesting that “the analysis of codes perhaps allows an easier and surer historical definition of a society than the analysis of its signifieds.” Without attempting to define virtual society, deconstructing some of the symbols seen within digital culture can investigate what they reveal about how we relate to expression through the simulated body.

Simulacra and Simulation

Jean Baudrillard’s 1981 treatise Simulacra and Simulation, translated and republished in 1995, claims that all current reality has been replaced with a collection of symbols and signs (simulacra), simulating human reality while erasing contact with the original world. This process is broken down into four stages, the last is where only simulacra exist, bearing no relationship to any original reality. This state, defined as hyperreality, is a “real without origin”, an artificially created world that has begun to erase the original. Nunes suggests that the internet achieves this hyperreality: it “abandons “the real” for the hyperreal by presenting an increasingly real simulation of a comprehensive and comprehensible world.” In Faux Expressionism, the emotive meaning represented by the digital movement we see online ceases to exist and is replaced by imagery itself. This reinforces the “mythic time” of cyborg embodiment, bringing us closer to a society where expression is minimised. In naming Faux Expressionism, we can examine how these new ways of moving reveal more about our current notions of humanity than previous modes of expressionist dance.

Curation and Corecore

A series of developments have pushed society even further into hyperreality: live-streaming, motion capture technology and the AI industry boom, alongside the surveillance cameras, search engines and self-tracking social media devices that generate daily digital representations of our bodies. In 1995, Nunes writes that “currently, writing is the dominant means of communication on the Internet”. In 2024, movement has a dominant, if not more pervasive presence than words online, with reels and TikToks becoming an everyday vernacular for self-expression. Human bodies and various choreographic materials attempt to convey meaning: slime ASMR content and domestic cooking videos evoke new feelings online. This presence of recorded movement goes against the suggestion of many dance scholars that “performance is defined by its ephemerality” and instead creates a platform where Faux Expressionism is revisited without the temporal confines of the original world.

In addition to the expressive choreographic material of digital media, Faux Expressionism can be observed as a curational and compositional tool. The “anti-fad” of corecore is a form of chaos edit, loosely defined as “similar and disparate visual and audio clips that are meant to evoke some form of emotion.”

A scroll through the TikTok tag reveals thousands of chaotically edited videos compiled with “no intrinsic meaning” transformed into “something that makes people feel”. Simultaneously, temporality is explored in new ways via digital content, for instance in the trend of sped-up and slowed-down remixes emerging on TikTok. Schmid discusses how “digital technologies are shaping our temporal experience and play a determining part in forming and reconfiguring us to who we are, as digital bodies.” The relentless pace of the virtual world is decelerated into a liminal realm where it can be better explored. These techniques concurrently emphasise and abstract emotion.

Conclusion

Faux Expressionism provides a framework within which movement and expression can be better understood, a way of processing the ceaseless stream of the choreographic material that digital content consists of. It can also create a playground, a realm in which this mode of expression can be adopted by the live body. The increasing synthesis of our virtual and physical forms means that Faux Expressionism is not contained to the two-dimensionality of our screens. In our cyborg reality, symbols appear in an indistinguishable feedback loop between online feeds and our daily interactions: movement is constantly translated between physical and digital bodies and contexts. This framework brings emotion to the foreground of our experience as content consumers and creators, whilst simultaneously expressing the huge disconnect between our embodied feelings and our language or ability to communicate beyond simulacra. This disconnection rationalises our ability to endlessly scroll through content, and experience the extremes of violence, hope, doom and humour in a way that is both abstract and affecting. In many ways, this disconnection is authentic to the contemporary human experience, and thus Faux Expressionism becomes a useful articulation of how the evolution of hyperspace heavily impacts our relationship to feeling, movement and curation. Situated within the context of cyborg embodiment, simulation and semiotics, Faux Expressionism is a way of viewing the connection between movement and expression as a constantly evolving relationship. As we edge towards a time of hyperreality, the ways in which movement is performed, curated and consumed provide a link to both the historic embodiment of emotion and a path towards the last stage of simulation where meaning ceases to exist entirely.

Bibliography

Auslander, P. (2011) Liveness: Performance in a mediatized culture. London: Routledge.

Barthes, R. (1977) Image, Music, Text. London: Fontana Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1995) Simulacra and Simulation. [Online] Translated by Glaser, S. F. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. Available at: https://0ducks.wordpress.com/wpcontent/uploads/2014/12/simulacra-and-simulation-by-jean-baudrillard.pdf. (Accessed: 25 June 2024).

Best, D. (1974) Expression in Movement & the Arts. A & C Black.

Carolan, J. (2022) 10 June. Bouncers should start doing this at bars #MadewithKAContest#genz #millenial #handheart #fyp.

Available at:

https://www.tiktok.com/@juliacarolann/video/7107380364053581098?lang=en&q=Julia%2 0carolan%20heart%20symbol&t=1721051816012 (Accessed: 15 July 2024).

Cruz, R., Harding, C. and Sloan, N. (2023) ‘Too Fast? We’re Curious: The sped up remix phenomenon’, Switched on Pop. [Podcast]. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4Oec5c7S8E16qBLpS7btMg?si=e93bcf4d1fb64a22.

(Accessed: 21 March 2024).

Frenkel, S. (2023) ‘The Changing Online Language of Hearts’, The New York Times [online], 14 February. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/14/technology/heartsemojis-gen-z.html#:~:text=Carolan%20demonstrated%20that%20if%20someone. (Accessed: 20 June 2024)

Haraway, D. (2016) A Cyborg Manifesto. [Online]. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Available at:

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fictionno wnarrativemediaandtheoryinthe21stcentury/manifestly_haraway_----

_a_cyborg_manifesto_science_technology_and_socialist-feminism_in_the_....pdf.

(Accessed: 19 June 2024).

Hayles, N.K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Laing, O. (2016) The Lonely City: adventures in the art of being alone. New York: Picador.

Lupton, D. (2017) ‘Digital Bodies’ in Silk, M., Andrews, D., & Thorpe, H. (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Physical Cultural Studies. London: Routledge, pp. 200-209.

Nunes, M. (1995) ‘Jean Baudrillard in Cyberspace: Internet, virtuality, and postmodernity’, Style, 29(2), pp. 314–327.

Phelan, P. (1993) Unmarked: the politics of performance. London; New York: Routledge.

Press-Reynolds, K. (2022) ‘This is corecore (we’re not kidding)’, No Bells, 29 November.

Available at: https://nobells.blog/corecore/. (Accessed: 20 June 2024).

Sebeok, T. (2001) Signs: An introduction to semiotics. [Online] Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Available at:

https://monoskop.org/images/0/07/Sebeok_Thomas_Signs_An_Introduction_to_Semiocs_2 nd_ed_2001.pdf (Accessed: 1 July 2024).

Steele, A. (2009) High Technology Dance: The image continuum – dance is meaning and message. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

Schmid, H. (2017) ‘The Embodiment of Time’, in Broadhurst, S. and Price, S. (eds.) Digital bodies/creativity and technology in the arts and humanities. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 97-111.

Townsend, C. (2023) ‘Explaining corecore: How TikTok’s newest trend may be a genuine gen-Z art form’, Mashable, 14 January. Available at: https://mashable.com/article/explaining-corecore-tiktok. (Accessed: 9 June 2024).